Wrong, Financial Times, the Arab Region Faces No Climate Emergency

By Linnea Lueken

A recent (paywalled) Financial Times (FT) article, “‘Too hot to handle’: climate change pushing Arab region to limits, says WMO,” claims that the Arab region is being simultaneously hammered both by increasing heatwaves, droughts, and paradoxically, more flooding, and extreme rainfall, all due to human use of fossil fuels. The FT’s story is misleading at best, and false at worst. While one World Meteorological Organization (WMO) report referenced by the FT does say that heatwaves have increased in the region, the data are not as alarming as FT frames it, and there is no evidence that giving up fossil fuels will help anyone.

FT reported that the Arab region, which they defined as the region from the Arabian peninsula and Levant to North Africa and Somalia, is “being pushed to its limits by intense heatwaves and severe droughts, the latest World Meteorological Organization report found, as it warms at twice the global average.”

FT did not actually link to the report in their piece, which was unfortunate, because it was interesting to read through. Luckily, it was not hard to find on the WMO website.

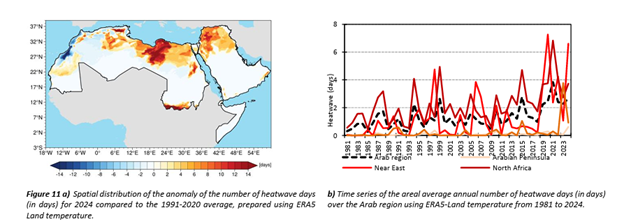

The areas in the report that are supposedly suffering the worst heatwaves are all places that are already famous for extreme heat; located in the hot, arid desert of North Africa. But even across that broad region, the most intense increase in the number of heatwave days in 2024, according to ERA5 land temperature data, compared to a 1991-2020 average, is 14 extra days in one area. Most of that data show no extra days of extreme heat across the region. To the West, there was a noted decline in heatwave days. The chart on the left, shown below, is also just for 2024, which the WMO admits was an El Niño year, which drives global temperatures up. Data for this year will almost certainly show more moderate temperatures.

Figure 1: From WMO report, https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69717-state-of-climate-in-the-arab-region-2024?offset=

It is also no wonder that the Arab region warms at “twice the global average,” as 70 percent of the globe is covered by oceans, where the air temperature rise has been generally much lower than over land. As such, it’s a meaningless statement, since almost all land areas will be on the higher side making up the global average. These kinds of statements are meant to provoke fear, and have little scientific value.

FT goes on to claim that the report “warned that drought conditions in the Arab region had been worsening, particularly in western north Africa, after six consecutive failed rainy seasons.”

This is an odd statement, since the “drought” section of the WMO report itself says “trend analysis does not indicate statistically significant changes in drought intensity across the subregions, suggesting that while drought remains a recurrent hazard, its long-term severity has remained relatively stable over the study period.” So on this point, the FT totally misrepresented the findings of the study they were citing as evidence for worsening drought.

It seems the FT writers did not go deeper than the “key messages” page at the very beginning of the report, which are somewhat misleading compared to the actual content of the full report.

Since climate change is a set of long-term phenomena, long term trends matter most, as shorter periods are just weather, which can become more or less severe from year to year, or even over the course of a decade or two, as the regions of the Earth have experienced throughout time immemorial.

FT added, “WMO secretary-general Celeste Saulo said intense heatwaves, where temperatures have hit 50C in some Arab countries, were “pushing society to the limits”.

While 122°F is definitely hot, it is also definitely not unprecedented across the region. An article at Weather Underground’s (the weather service, not the terror group) blog describes an all-time “reliable” temperature measured in Algeria of 124°F in 2018, and explains that older recorded highs are questionable because of spotty recording quality. The Arabic region was less developed than Europe, for instance, in even the early twentieth century, which means records have a shorter time span.

Funnily enough, FT is willing to call this year’s cooling natural: “this year is expected to be among the top three warmest despite the cooling effect of the naturally occurring La Niña cycle in the Pacific Ocean.”

El Niño is glaringly unmentioned in the article, despite being responsible for 2024’s temperature spike.

With regards to flooding and precipitation, the WMO identifies no trend in rainfall or flooding across the Arabian region. Breaking it down into sub-regions, East Africa has seen an increase in average annual precipitation, while North Africa began to see a decline since 2010.